Life is more than cause and effect.

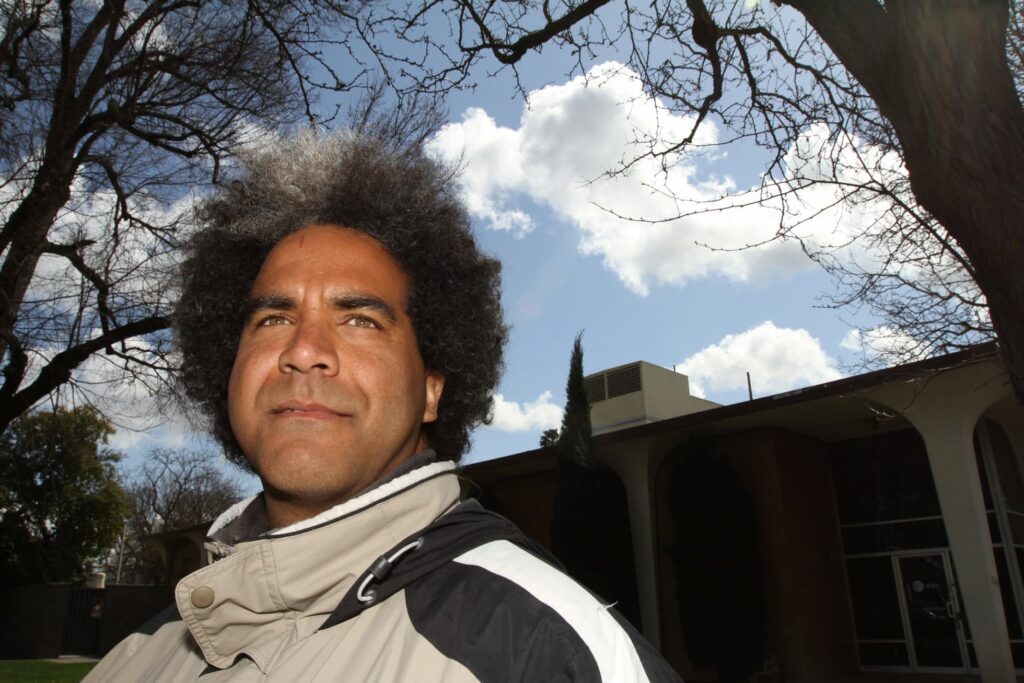

I decided to write this piece after reading the article about the murder of David Breaux (pictured above), also known as the “compassion guy,” a regular fixture in the UC Davis park. Breaux, a Jamaican immigrant, and Stanford graduate, shunned the typical path of finding a cushy job after graduating and instead decided to lead a purposeful life of “compassion.” He slept on friends’ couches and in shelters and survived on their kindness. He also slept on park benches, which is where he was found stabbed to death; the act of a probably mentally disturbed man, who also killed Davis senior Karim Abou Najim before he was caught.

Reading about Breaux’s senseless murder made me, like many others, confront the question, “Why do bad things happen to good people?” We are reared on the cause-and-effect code of ethics; good people go to heaven, the evil go to hell. But conveniently, there is no way to test this hypothesis. Laws dispense justice in some apparent transgressions. In this case, the murderer will go to prison for life, but that is no consolation to understand why a good man like David met such a gory end.

As a Hindu, I was raised on the infallible reincarnation principle. Good people suffered because they were paying for the sins of their previous birth. Or an evil man’s misdeeds will surely be punished in his next birth, in case he managed to get away scot-free in this lifetime. Like the heaven and hell argument, the rebirth hypothesis is also impossible to test. But human beings are wired for justice, and these cause-and-effect arguments are powerful in moral policing and, therefore, cleverly cloaked as religious tenets. Along these lines, we can justify David Beaux’s death, saying he’s in heaven and has successfully ended his endless cycle of rebirths. Moreover, good people are always called up early because God needs them.

But should David Breaux be defined by his death? That’s a disservice to his memory because his “life” can teach us many lessons about how we should live. David’s life is proof that we cannot control everything. Although we try to deal with life’s uncertainties with religion, science, or probability, the only certainty is death, so why not live a life you believe in? Not everyone has the luxury of living as they please, but aspiring for inner harmony is a worthwhile lifelong goal. However, taking that route takes courage, of which Breaux is an exemplar. He did it his way, failures and all.

David’s life proves that the universe owes you nothing except the gift of life for however long it lasts. So why mope instead of making the most of the fleeting moments granted to you? David’s impact in his brief stint on this earth is remarkable. To quote a famous proverb, “It’s the life in your years that count, not the years in your life.”

But the world needs positive and just examples, and for this, we must broaden the context beyond David’s life, as he’d strived all his life. David died a martyr, opening our eyes to the senselessness around us. At least momentarily, he put us in touch with our humanity. From the comments on the NYT article; many, like me, immediately bought his book on compassion; UC Davis students fondly shared their memories of meeting him in the park, and other readers genuinely mourned him. David had brought people together in an unadulterated outpouring of compassion in our distracted and disconnected world.

But eventually, there is no answer for why bad things happen to good people. The problem lies with the question and our punishment-reward mode of moral education, starting with Santa Claus. The appropriate question is, why should you be good? David’s life provides the answers. Be good because you want to and because there is no other way. Be good because it makes your heart swell, and your spirits soar. Be good, so you like the person you see in the mirror.

When Gandhi died, George Orwell, who supposedly disliked him, wrote that despite being a politician, Gandhi left a clean scent. On a smaller scale, David left behind a gentle, sweet perfume.