One-line review: A genius who just wants to be.

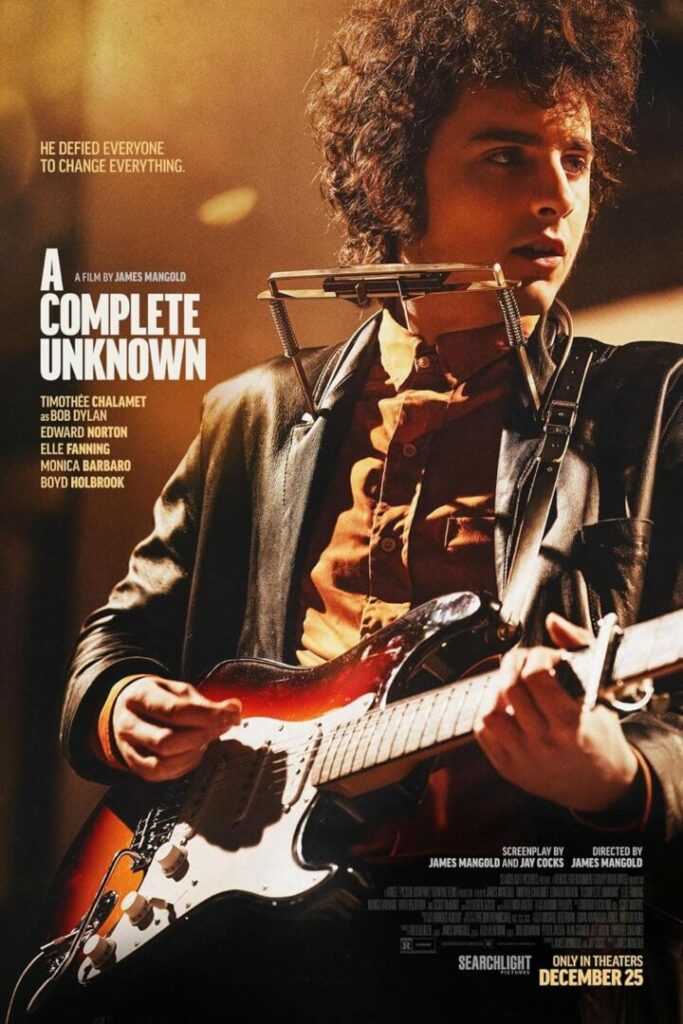

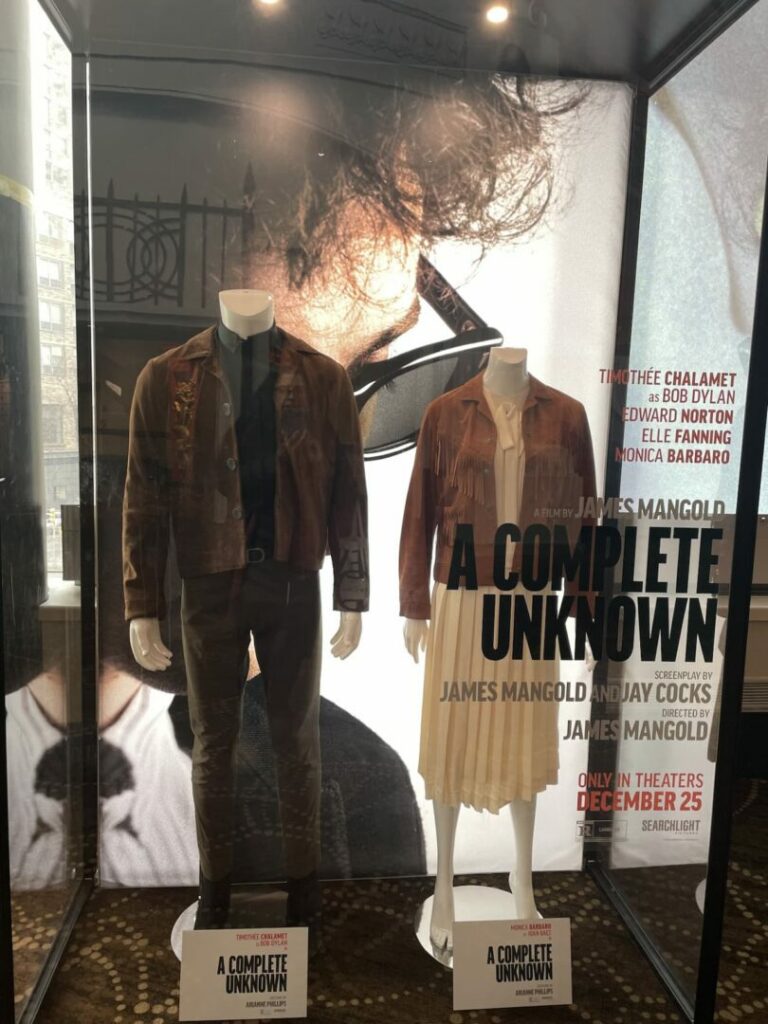

I have now seen this Bob Dylan movie seven times and in all formats: IMAX, Dolby, Laser, you name it, and I can’t wait to own it. It’s just a great movie that delivers on all departments: script, directing, casting (even the guy who announces Seeger at the open mic is unforgettable with his toothy bashful grin), performances, music, sound, editing, and costumes. Director James Mangold, who also wrote the script after an initial draft by Jay Cocks (based on Elijah Wald’s book), cleverly keeps the film’s focus on a few crucial action-packed years in young Dylan’s life. And he can do this because Dylan rose from a nobody to a superstar messiah in three years. This focus also allows him to cast a superlative Timothee Chalamet at his prime. In my humble opinion, this was also when Dylan sang melodiously without his unbearable nasal twang.

Interestingly, the directors of the two big movies of the year, A Complete Unknown and The Brutalist, Mangold, and Brady Corbet, say their films’ underlying theme is the Salieri- Mozart dynamic. It’s easy to see the connection in the Brutalist, but it is less evident in Dylan’s life since so many people surround him. But honing in on this theme gives the film its coherence. Mangold (he considers Amadeus director Miloš” Forman, his mentor) says the film is about how people (even successful ones) cope or don’t when a young genius suddenly appears in their midst, making them face their mediocrity. One of the important people in Dylan’s life those days, Joan Baez, seems to hurt after all these years and says the film correctly captures how Dylan would suck the air out of any room he entered, relegating everyone else to the background. In one of the most poignant lines of the film, Dylan complains that people are not interested in knowing how he writes his sublime songs effortlessly. Instead, they want to know why they can’t do it. That’s the gist of the dynamic between Dylan and the others.

The film starts with a young Dylan arriving in New York to meet his idol, Woodie Guthrie (Scoot McNairy; memorable despite his movement constraints), who is in hospital permanently because of Huntington’s disease. It’s a happy coincidence that Peter Seeger (Edward Norton) is also visiting him then. Seeing Dylan’s guitar, they ask him to sing something, and he sings the “Song to Woody.” Both men realize they have seen something special. This scene was one of the most moving scenes in the film for me, both for Chalamet’s performance and for what it meant. The change of guard in folk music was happening in an insignificant hospital room. It is a clever scene because it gives us many insights into an otherwise inscrutable Dylan. We also see his soft side because the rest of the film shows his, at times, cruel streak. The man knew and respected his history.

Dylan was at the right place and time, armed with his genius. Fate also intervened with the support of many good people who wanted him to succeed, especially the selfless Peter Seeger. Ed Norton’s earnestness and large-heartedness as Seeger are a perfect foil for the bristly Chalamet. Others include his agent Albert Grossman (a fine Dan Fogler) and his pure white lily of a girlfriend, Sylvie (Elle Fanning). It is rumored that Sylvie (real name Suzie Rotolo) was responsible for introducing Dylan to the social justice movements. Fanning is the only misstep in the movie with her one-dimensional portrayal of Susie. I wonder whether it was Mangold’s directive to show Sylvie in tears during all of Dylan’s breakthrough moments; it makes her come across as selfish rather than insecure. Thankfully, Fanning’s abundant charm rises above her tears. On the other hand, Eriko Hatsune, who plays Toshi, Seeger’s wife, makes more of an impression with her expressive face, although she barely has any lines and has to play the single note supportive, pained wife.

We see a bashful Dylan develop his swag after his almost instant success; it’s a shield as much as a sign of confidence. Although he shunned being labeled, Mangold says Dylan didn’t expect singing to be lonely and wanted to be part of a group, a band; he’s only twenty, for heaven’s sake. What’s mistaken for arrogance is just a young man seeking out friends his age. Another person in his orbit this time is Joan Baez, played by a splendid Monica Barbaro, who finds herself being overshadowed both personally and professionally by Dylan (the film doesn’t show how Dylan, after getting his early breaks because of Joan, doesn’t invite her to sing with him in his popular days). Barboro expertly treads the fine line between power and vulnerability and emerges on the right side; she owes it to Baez’s fans and women in general. Another ally who understands what Dylan is going through is Johnny Cash, played by a spectacular Boyd Holbrook, who is unforgettable despite his short screen time.

The film shows us snippets of Dylan’s unmistakable talent, including his appearance at Seeger’s radio show, where he riffs with blues player Jesse Mofette (an excellent Big Bill Morganfield who brings the much-needed levity as the proceedings get serious), and his various sold-out concerts, including the rousing “The Times are a changing.” Showing that journey is essential to establish Dylan’s credibility with the audience. Mangold ensures Dylan has earned his stripes, so we are ready for one of the most sensational climaxes in recent films.

Mangold builds up the climax for the Newport Folk Festival. Its curmudgeon organizers, including Seeger, believe there’s no place for an electric guitar in folk music and are determined to keep folk music pure. They’ve heard Dylan plans to go electric, but Dylan remains tight-lipped (he’s the closing act). Dylan and his band (Charlie Tahan is the casting coup here as Al Cooper) enter without even looking at the audience and belt out three songs with Dylan on the electric guitar. The sound and music during this scene are still thrilling when you think about it; it’s also an editing marvel (Andrew Buckland and Scott Morris). It’s a spectacle with pulsating music, rising tempers, attempts at sabotage, and fights. But change is inevitable, as the sound guys tell the organizers, “Open your ears, man.’ Chalamet’s swag in the scene elevates it another notch. It’s moving that despite all the hostility from the audience, Dylan, the genius, is forgiven and forgives on the spot and returns to sing a good ole folk song with an acoustic guitar.

In another masterstroke, instead of ending on this high, Mangold ends the film meditatively. We see the aftermath of the Newport festival; everyone has left, and Pete Seeger is loading chairs, a strangely emotional moment we can all relate to, the emptiness in the morning when all the guests have left. Stoic as ever, Dylan makes his probably last trip to see Woody Guthrie, and a tender moment ensues between them. Guthrie’s evocative song as Dylan rides into the sunrise closes out the film.

The film’s spine is, of course, the sublime Timothée Chalamet. Adrian Brody looks like the front-runner for the Best Actor Oscar, but Chalamet’s role, though lighter on the surface, requires an insane level of preparation. All the songs were sung live to a live audience. Another detail that becomes more astonishing with repeated watching is how Dylan’s posture and swag change as success brings him more confidence. Add to this Chalamet’s magnetic expressive face; you realize why this man couldn’t shake people off despite trying and why all the women wanted to take care of him.

I have seen many people comment on having seen the movie multiple times or wanting to go back. I think that’s because the film allows you to be a part of those times when excellence and character reigned supreme.