I spent my childhood summers with my grandmother in Kollam, Kerala. As I grew older, around eight or nine, my parents dropped me off and returned to the nearby city of Kochi, where we lived. My grandmother lived in a traditional house with a courtyard (sadly dilapidated now) with my widowed aunt and a maid. My aunt, a high-ranking government official, was one of the few women in the village with a full-time job. She would be away all day and retire to her room after dinner, as would my grandmother. So, I had a lot of time on my hands in the evenings since these were pre-television days in India.

My grandmother’s house had a large prayer room with the idols of most Hindu gods, and interestingly, Jesus received a place of pride, too. A wooden cupboard in the prayer room contained my aunts’ textbooks. My mother was the middle sister, whose older and younger sisters went to college, a rarity in those days. I don’t know why my mother didn’t go to college, but there were rumors that she flunked high school. This was clearly a sore point in the family because although my grandmother’s living room walls were lined with pictures, my aunts’ graduation pictures were conspicuously absent out of respect for my mother.

This cupboard of my aunts’ books was my playground. It mainly contained Malayalam books, but there was a sizable collection of English books. Looking back, the array of English books was impressive, ranging from Maxim Gorky’s “Mother,” John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, and Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights. Although I tried reading all of them, they were beyond my comprehension. But nine-year-old me found immense joy arranging, indexing, and rearranging these books. Each book would be lovingly examined, dusted, and placed back on the shelves. I then made a list of the books, signed it, and stuck it on the cupboard’s inner door. Each time I visited my grandmother, I would painstakingly examine the books and the list, although no one else opened the cupboard except me.

Soon, I noticed several books were by the author Pearl S. Buck. Thinking she might be an influential author, I tried to read some of them. I started with The Good Earth, and although I couldn’t understand much of it, I was fascinated by the Chinese farmer’s rice and cabbage meal. We ate cabbage occasionally, too, but it was just one of the many dishes in a meal that included rice, lentils, and fish. So the farmer only eating rice and cabbage for dinner and out of a bowl, as opposed to a plate, was fascinating. That must be some delicious cabbage, I remember thinking.

And then, I stumbled upon Pearl S. Buck’s “Portrait of a Marriage.” It is a slim book and the story of a wealthy artist, William, who falls in love with a country girl, Ruth, and their long marriage until his death. It was surprisingly easy enough for a nine-year-old to read. I didn’t understand the book’s larger themes of class and wealth differences, but the love story was clear. The uneducated but practical Ruth was almost like bread for dreamy William’s sustenance. Ruth gardened and smelled of roses, perhaps the reason for my intense love for roses and rose perfumes. I read the book several times over the years; picking up the book was like playing with an old friend. A secret friend because my parents would disapprove of a nine-year-old reading a romance novel. Soon, I moved on to Mills and Boon romances, but the mature and long-lasting love in Portrait of a Marriage lingered.

Years later, I moved to the US, lived in Philadelphia, and heard about Bucks County. I checked if the place had any connection to Pearl S. Buck, and indeed, it did. I was surprised that many of my American friends had no idea who she was. Visiting her house in Bucks County was always a dream, and it finally happened in April 2024. I went with my friend Mark, who is from the area, but didn’t know who she was. We stopped at Doylestown’s charming Hattery Stove and Still for a homely yet unique brunch; the chocolate gnocchis were the highlight.

Soon, we were at Pearl S. Buck’s sprawling estate, and it felt like the end of a pilgrimage. I wished my aunts were alive to share this moment. There were hardly any visitors there, and our guide, a charming professor, seemed thrilled to take around someone almost reverential to Pearl S. Buck. I discovered that the connection between Bucks County and Pearl S. Buck was sheer coincidence because she was born in Virginia. After divorcing her first husband, John Lossing Buck, Pearl moved back to the US from China. She wanted a large property close enough to her New York publisher, Richard Walsh (whom she later married). She chose this sprawling property in Bucks County, which she bought for $5000 in 1935. Pearl decided to keep her first husband’s last name, and it was an intelligent woman thinking about posterity; what could be more natural today than Pearl S. Buck from Bucks County?

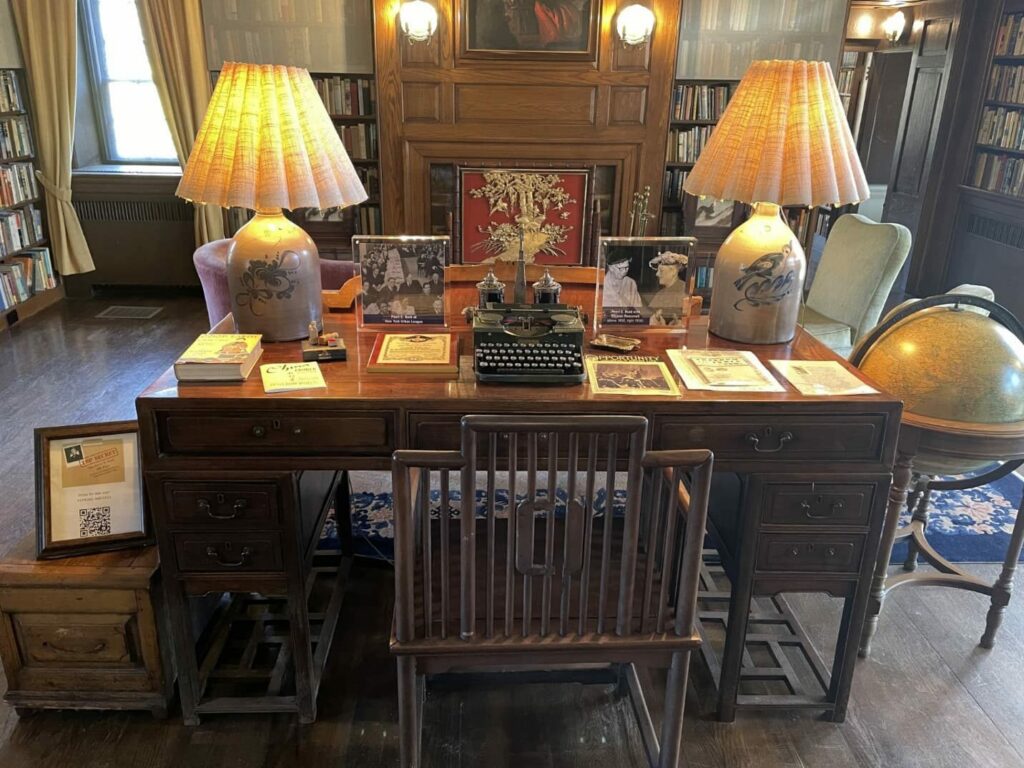

Most often, we are disappointed by the people we idolize. But Pearl S. Buck, who for me until then was a larger-than-life author of my favorite childhood book, proved to be even more spectacular. She was a force of nature, a pioneer in the truest sense. Especially her championing of intercultural understanding through adoptions, and this when she claimed not to have maternal instincts (she did not have biological children with her second husband, although he wanted to). Her only biological child, Carol, had the then undiagnosable disease, Phenylketonuria, that left her mentally disabled. Carol moved to a home for people with disabilities, where she defied all odds and lived until her seventies. Pearl set up a trust to ensure she always had the funds for her upkeep. It was fascinating to see her kitchen, dining table and china, extensive library, and the desk on which she wrote The Good Earth. But I was most moved to see the little heater by her bedroom to warm milk for her many adopted children, who had tidy little rooms next to her main bedroom.

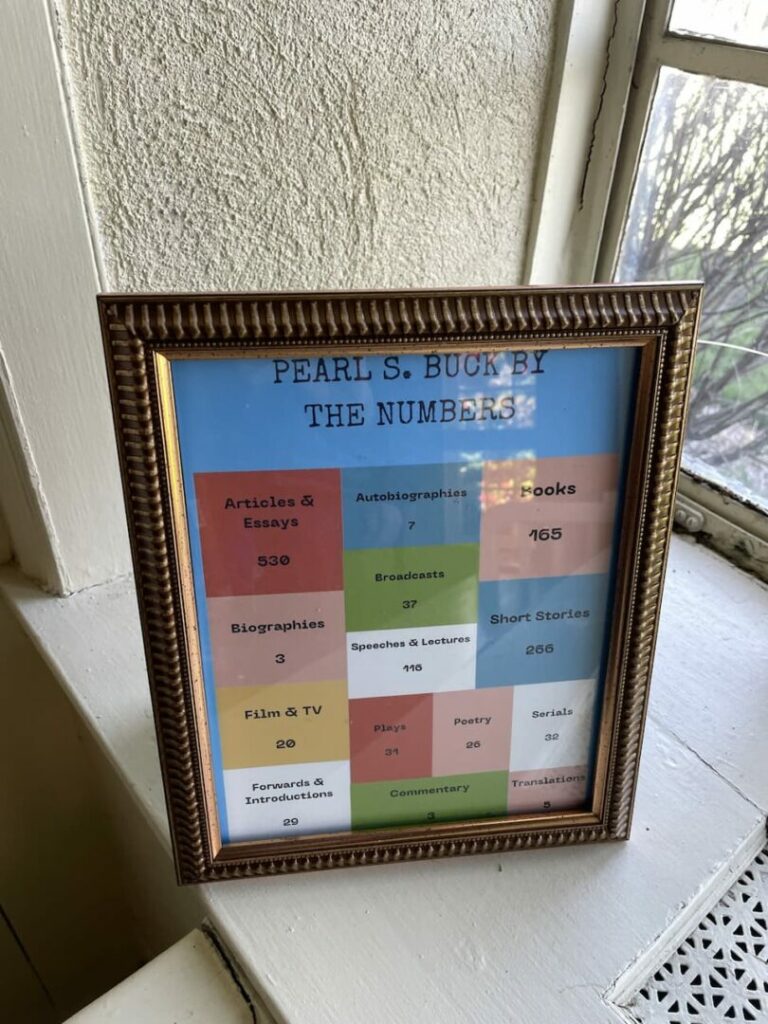

But my most important takeaway was that Pearl was a working writer with an impeccable work ethic. She was immensely prolific, leading many envious male authors to question her work’s quality unfairly. Like any other occupation, Pearl believed writing was work and how she earned her living. It always warms my heart when I see women’s offices occupying a place of pride compared to the men’s. Pearl had a better and bigger office than her second husband, Richard Walsh. Sadly, he suffered a stroke twenty years into their marriage, and she cared for him in her house until his death. Pearl was also a socialite, and her vast collection of coats and dresses was also on display. Pearl’s adoption center is now closed, and her society must keep interest in her alive. Thankfully, the government funds will keep coming since the estate is a national monument.

We ended our tour by stopping at her grave (she died from lung cancer in 1973, at eighty). As I stood by her grave hooded by trees, I remembered Lin Manuel Miranda’s lines from Hamilton, “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story?” Who would have thought that Pearl S. Buck, mostly unknown to her neighbors, would profoundly affect a little girl in a remote village in South India? I also remembered my dear aunts fondly. When they put away their college books, little did they know their little niece would find solace in them, discover Pearl S. Buck, and eventually visit her resting place. They would be proud.